Each song from the album will be accompanied here with a story. For the lyrics, click on the title of the song.

It was All Saints Night and the streets were thick with

fog, of that I'm positive. The sounds from

the Harbor rang still and with muffled tones. The tavern was warm and

inviting, while outside a

grey mist drenched the exhausted city. The times were troubled and the

streets unsafe; and yet, I

felt the need to be away from the forced gaiety of that anxious crowd.

The stranger was on the

front step as I opened the door. I did not catch a glimpse of his face

- his head was covered by a

cowl-like hood. But there was, about him, something that caught my attention.

Later that

evening, I was shocked to see him again on a corner of Christopher, a

stone's throw

from the River. He did not fit well in his surroundings but, for that

matter, neither did I. I

watched him from across the street. He was framed in an arc of gaslight.

I could have sworn that

he was talking to someone but I am certain there was no one there. His

eyes appeared to be

tracking shadows up the cobbled lanes that spiral off that street of dreams

- or nightmares, as the

case may be.

I was not

surprised to see him in St. Malachy's. An acquaintance of mine was being

waked - a

distinguished actor who had cut a figure on the stages of Europe; his

last encore had drawn a

diffuse, if somewhat bohemian, crowd and so my cloaked and hooded nemesis

did not seem out of

place. He stood in the cold shadows at the back of the pews, lifeless

except for eyes that burned

with some intensity at a crucified Jesus suspended over the main altar.

At one point, my attention

was distracted but when I looked again he was in animated conversation

with a tall, distinguished

Jewish gentleman. I thought of introducing myself but decided it was neither

the time nor the

place.

At midnight,

I found myself back down by the pier side. Trinity's bells were pealing

the lateness

of the hour when I noticed him again. He was speaking to a beautiful woman

with long, coarse

dark hair that cascaded well below the small of her back. Dressed in a

fashion not of this century,

she was forlornly gripping him by the arm, her face white as Holland sheets.

I hid in a doorway,

unwilling to trespass on their intimacy but pivoted my body for a better

view. From time to time,

he would glance in fear or annoyance at a uniformed figure that seemed

to be beckoning to him

from the bow of a ship. My friend, for by now I thought of him as such,

appeared to be in two

minds. When suddenly, he seemed to bristle at the sight of the Jewish

gentleman advancing down

the quayside. He bent and tenderly kissed the young woman with a degree

of loss and passion

unusual for these times; then again, perhaps I am surmising - for he had

his back turned to me.

She clung to him as if her life depended on it but he was resolute and

his footstep was deliberate

as he mounted the gangway to the ship. Near the top, he turned to look

back at her and the hood

slipped from his head. To this day, I shiver when I recall the scene -

for I knew that face only too

well.

Rain in

her hair, rain on her face, rain delineating the soft curves of her body;

it had rained steadily

for days now, but it was the rain in her eyes that arrested my attention.

Unlike a woman on a

naked city street, she made no attempt, subtle or otherwise, to hide these

tears. It was plain to

see that she'd suffered some great hurt but, out here in the country,

with no prying eyes upon her,

what need to conceal despair? The linnets would hardly notice. The sly

fox lurking by the

dripping willow had other things on his mind.

And so I

watched her from my window. She halted under the great beech tree and

stared off into

the distance. Then, with a start, she snapped out of her sorrow and glanced

towards the paddock.

A thrush was bitterly protesting the arrival of the brown mare and her

foal. Foolish thing, to build

its nest near that sheltering ditch. What kind of bird hides its young

in the ground anyway?

I strode

out on the verandah and pretended to admire the heavy peonies that grace

our garden

every June. I wanted to give her time to take in my presence. After a

few moments, she walked

towards me, the thrush forgotten but the hurt, like a bruise, still beaming

from her brow. I don't

remember what we talked about. It didn't matter.

I had no idea she was a junky when our paths first crossed; which is odd, because I was far from naive in these matters. I was living on 9th Street, just off A, back when Tomkins Square was Needle Park and, needless to say, I had already been well ripped off, lied to and promised the moon. I guess she just didn't look like the people I knew on dope. They were pale, treacherous creatures, thin as rails, either eerily silent or whining to beat the band - talk about "feasting with panthers." They're all dead now; AIDS took them - it was an East Village badge of honor that you shared your spike.

Josie was different. She had a great figure and her cheeks hadn't quite

lost their Mid-West rosiness. Unlike the other walking dead, she never

whined, definitely didn't use any Third Street slang and thought CBGBs

was the pits - though she had a sneaking fondness for Johnny Thunders,

but that's another story. She also took pride in her appearance, dressed

with a thrift shop flair and, up to the end, kept her day job. I suppose,

too, I was blinded. When you have designs of your own they tend to varnish

even the truest of mirrors. Still, I should have seen the signs.

We just seemed so right for each other. I'd never met a woman before who

loved Lawrence Durrell, nor someone who had her own LPs of Five Leaves

Left and Astral Weeks. She based her dreams on the Quartet, while Nick

and Van kicked in the sound track of her life. At first, we talked all

the time - the sheer relief of meeting someone who shared the same joys

and interests. Then, we talked less but I felt that we had reached an

understanding and that words were no longer necessary. In the end, we

barely spoke at all. I hope she's still alive, living a suburban life

in Chicago or Cleveland or wherever she disappeared to. But, I somehow

doubt it.

Click here to download this track

After we'd meet she always insisted that I walk her back to the café where he'd be waiting for her, sitting there in his blind man's shades, dissecting and categorizing the world through dark and dimming eyes. He must have known the shape of her body so well because, even at ten yards, he'd rise to greet her, arms outstretched and then carve his kiss of possession on both her cheeks. He'd bow to me, very gravely shake my hand and inquire if I'd care to join them. I could never help but feel that I was part of some very elaborate charade.

She'd recite the usual litany of lies, alibis and excuses and he'd sip

his white wine and nod in his world-weary, but alert, manner. At times,

he drove me mad. He must have known what was going on. Why didn't he say

something? Then as the dusk dissolved into the bitterness of night she'd

move closer to him until I could have sworn that she too was about to

disappear....into him.

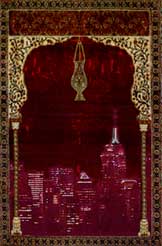

A couple of years back, I overheard Pete Hamill, raise a question. Now for those of you unfamiliar with the man, Pete is the epitome of much that is great about New York City - a wonderful writer and straight-talking man-about-town with a heart of gold, a reverence for the past but an unquestioning openness to change. The question, as I remember it, was, "what does the Pakistani cabdriver say to his children when he goes home at night?" Simple, I suppose, but elementally profound.

Pete is the son of Irish immigrants to Brooklyn. Thus, not only can he

empathize with the sense of displacement his parents must have felt but

he has written eloquently of the clash between family tradition and the

overwhelming attractions of the new world. Unlike many others, however,

Pete has always resisted some of the more xenophobic tribal loyalties

that often promote hostility to those further down the rungs of the immigration

ladder.

You can learn a lot about a city by observing its taxi-drivers. When I

first came to New York, cab driving was an accepted way for young white

heads to make a buck. You could choose your work hours and spend the rest

of your time studying, playing music or just plain hanging out. In that

era, young African-Americans also drove for a living - a rarity now. Then

Haitians seemed to be the ones you noticed - where have they all gone?

And now, it's Pakistanis, Bangladeshis, Sikhs and people from the former

USSR, with a generous sprinkling of other recent arriving groups.

But it's the Muslim drivers who fascinate me. Some seem to be still reeling

from the shock of secular America. And secular America, in its turn, reacts

accordingly. For, their religion can seem completely inimical to Mom and

Apple Pie, while the fundamentalists amongst them can indeed appear formidable.

Yet, if you show the least interest in their culture, they can open your

eyes to worlds beyond our experience. Though their ways may seems strange,

yet there is a comfort and regularity to their religion that reminds me

of happy, unquestioning days of boyhood when I totally believed in a bedrock

Catholicism knit together by saints, martyrs, mysticism and the certainty

of salvation. Where did that go?

Two instances come to mind from travel in the Muslim world. One night,

in a village square in Southeastern Turkey, close to the Syrian border,

I came upon a blind "saint" around whom a crowd had gathered.

He stood there, immovable as an oak, tall and turbaned, his skin as creased

as old bark, a vision from another time. He seemed to be waiting for something

- some sign from within or without - I didn't have the facility to judge.

Then he began to rock back and forth as he intoned some ancient melody

in a language I didn't recognize; at first, his voice seemed to come from

somewhere deep down and I'm not just talking about physicality. Then it

poured forth like honey over rusty nails. The large crowd, for by now

it had filled the square, lapsed into silence and we all became as one,

while this man from another time, took us back there with him.

The other memory is of being outside a mosque, in a cool, lavender dawn,

while the muezzin summoned the city to morning prayer. The men arrived

silently and began to wash themselves in cisterns of fresh running water.

It was all very orderly and quite systematic - this preparation for prayer

in the new day, the first of their five alignments with God. I envied

them their quiet certainty - so far removed from the stultifying crassness

of consumer culture.

And so, to Fatima. I've left her story purposely unfinished. Will Brooklyn

Michael be able to rise above his ignorance of other worlds, come to terms

with her family and its traditions and, in so doing, become a real man

himself? Hardly likely, I suppose. And still, one hopes against hope.

Or will Fatima, for love of her Father, accept an arranged marriage? Will

another Michael come along and rekindle her rebellion? Could she live

happily with him, away from the warmth of God, hearth and family? Or instead,

will she meet someone who will keep the holy ways while still managing

to repair the things inside her that must continue to fall apart in America?

I don't know but I wish her happiness.